Further Reading: Formation of EVP

Abstract

Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVP) can occur in a number of different ways. Knowing how the voices are formed, or at least where in the circuit, might help researchers design more effective devices and help avoid false positives. This article is intended to explore the various methodologies used in EVP experimentation. It is not intended to select one technology or methodology over another or to discourage research in what might appear to be a less productive approach. The main intent is to understand voice formation so as to avoid mistaking and reporting mundane signals as phenomenal.

Introduction

This article is intended to frame the discussion of where EVP are formed in the technology and how to detect and avoid false positive results. It is an attempt to deal with the subject in an analytical format without making unsubstantiated comments. Based on this and similar articles, best practices will be proposed under the Practices Tab of ATransC.org..

Transform EVP

The most common technique for EVP experimentation is the use of an audio recorder, and if necessary, a background sound source. Transform EVP are not an acoustical phenomenon, and so are not heard at the input of the electronic device. In some recorders, it is possible to listen to the signal as it is saved to memory; however, there are problems with experimenter comprehension that usually makes this “real time” approach impractical.

There is a substantial body of evidence based on well-designed research, and years of anecdotal reports, indicating that this form of EVP is the result of a transformation, within an electronic device, of available audio-frequency energy into a simulation of human speech. (1) This research has produced a list of characteristics for EVP that can be considered a “litmus test” that provides a means of avoiding mundane sound being mistaken as phenomena. (2) (See: Characteristic test for EVP) The current working hypothesis for how the voice is actually formed maintains that a small signal “message” is amplified via the action of stochastic resonance on the audio signal caused by background noise. (3)

Sources for a “Message” in Transform EVP

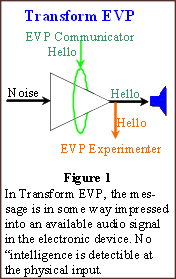

The EVP recording technique of using an audio recorder, and if necessary, supplying audio-frequency noise will be referred to here as the “basic recorder technique.” This technique is intended to produce transform EVP, but there are two other possible results. Figure 1 shows the intended mode, in which the EVP communicator somehow injects an utterance into the electronic device. The utterance exists in the output and the experimenter hears what is said.

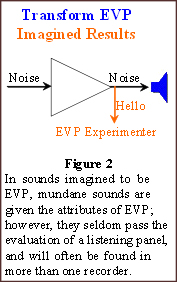

A second result that can be encountered is illustrated in Figure 2. The experimenter mistakes mundane sounds in the recording as being paranormal utterances. This is the common human response referred to as “pareidolia” (4) by the skeptical community.

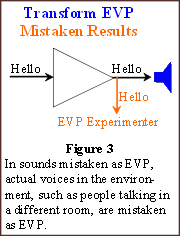

A third result is the accidental recording of unnoticed voices, for instance, someone speaking in the next room. When the recording is played back, the mundane voices are mistaken as EVP. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

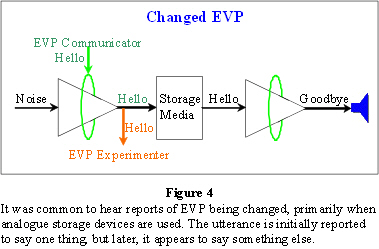

A fourth result is more of a possible characteristic than a different result, but it is listed here because of the apparent origin of a new utterance. This is illustrated in Figure 4. An EVP is recorded in the usual manner and is stored in either digital or analog media. When it is played at a later time, the utterance thought to have been recorded is apparently replaced with another or transfigured to say something else. Reports of this were more common when analog and magnetic tape was the storage media. It has also been reported that, once digitized, the EVP remains unchanged whether it is stored in magnetic media or transistor devices.

Figure 4 is representative of a block diagram for any recording device, in that there is an analog input stage which has an output that is the input to a storage mechanism. If the recording is to be heard by human ears, recovery from the storage mechanism is via a second or “output” analog stage. EVP is thought to be formed in analog processes, as (I believe) stochastic resonance does not work in digitized signals. Also the energy well for nonlinear digitized signals is considerably greater than for linear analog and should require considerably more energy to influence. (This is conjecture.)

If the recording is transferred to a computer by connecting the earphone jack of the recorder to the line in jack of the computer, even if it was initially stored in a digital format, it is converted into analog and passes through two analog stages before being digitized for storage in the computer. If the recording is transferred via an all-digital format, say with a USB cable, then it remains digital until it is converted to analog for playback. Thus using a USB interface eliminates two analog stages, and therefore should offer less opportunity for etheric influence.

Close examination of “changed EVP” has shown that there is a likelihood that the utterance only seems to be changed. Class C and many Class B examples can seem to change when the experimenter leaves the recording for a time and then returns to it with a different perspective.

Assuming that EVP does not occur in digital format, each playback will begin with the same sound file once it has been digitized. If the output seems to be different, then it must be different in the same way on each playback. If the recording is stored in magnetic media in an analog format, there is less certainty that the recording cannot be changed in the magnetic media.

The problem of changed utterances is one that is not commonly reported, but such reports should be carefully documented as to the technical circumstances. Analysis of such reports may offer insights as to how EVP are formed.

Transform EVP Summary

Four possible results of using the basic recorder technique are that an EVP will be formed out of available noise (Figure 1), the experimenter might mistake mundane sound as EVP (Figure 2), unnoticed conversations in the recording environment might be mistaken as EVP (Figure 3) and an existing recording might be changed in storage or on output (Figure 4). All of the transform EVP techniques we are aware of are based on voice formation out of available audio-frequency energy, within an electronic circuit. Variations of this theme only represent novel ways to condition the audio-frequency noise used for voice formation.

Opportunistic EVP

This category of EVP is relatively new and much less understood as compared to transform EVP. Opportunistic EVP devices usually have additional electronic stages which are different than what is found in the basic recorder technique using just an audio recorder and sound source. It therefore has additional ways in which an EVP might be formed. There are many variations on the theme represented by Radio-sweep technology, popularly known as “ghost boxes” or “spirit boxes” and EVPmaker.

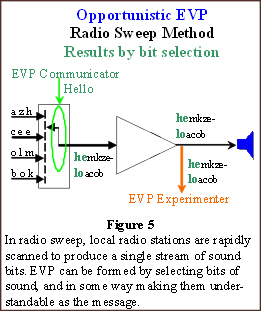

As is illustrated in Figure 5, radio-sweep involves rapidly scanning available Amplitude Modulation (AM) radio stations to create a single stream of sound fragments. The sound fragments are then used as an input to a recording device. In some applications, a speaker is also attached to the output of the sweep stage in an attempt to achieve real-time communication. Although it is possible to simply turn the tuner on a radio with a recorder microphone nearby, there are a number of “boxes” designed by inventors, such as the MiniBox (5) and Frank’s Box. (6) From our observations, these are all variations of essentially the same theme with different mechanizing techniques.

The software program, EVPmaker (7) developed by Stefan Bion, is also opportunistic in that a single stream of conversation is chopped into small bits and then reassembled into a second stream of sound made by concatenating bits based on a random number process. Bion’s research has shown that message formation is caused by manipulation of the random number process.

These techniques are called “Opportunistic EVP” because it appears that the EVP is formed by selecting available sound bits to form a word or sound that closely matches the intended utterance. This is different from changing sound to match the required output.

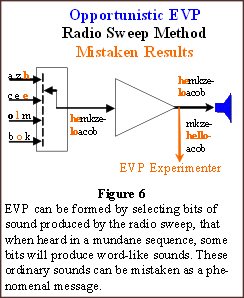

Figure 6 illustrates what is being referred to as Mistaken, Opportunistic EVP. As in transform EVP, mistaken EVP in radio-sweep and EVPmaker result from the assigning of meaning where there is none intended. Because the resulting stream of sound bits does have voice, it is easy for the mind to assign meaning to word-like sounds, even though none was intended or a second listener might hear something very different. The meaning is not caused by a communicating entity, but is from the tendency of the mind to find meaning in otherwise random sounds.

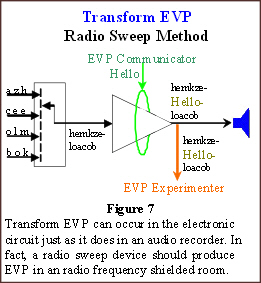

Figure 7 illustrates how the analog stage might be used to induce a transform EVP into a radio-sweep or EVPmaker circuit. Transform EVP in this circuit will tend to be interrupted by the sound bits from the radio-sweep, causing an effect similar to an experimenter talking over an utterance in the basic recorder technique. EVPmaker is not as likely to produce a transform EVP because all of the processing is in the digital format and the output is usually the only analog stage.

Opportunistic EVP Summary

EVP may be formed in the sound stream resulting from the fragmentation of a mundane source, either pre-recorded conversation in EVPmaker or multiple radio stations in radio-sweep. The resulting sound stream might also be mistaken as EVP when there is none, but transform EVP might be formed in the device. In concept, all of the opportunistic EVP devices depend on the sound frequency, amplitude and inflection to be present in the raw source at the time it is required for voice formation.

Selective reporting of EVP

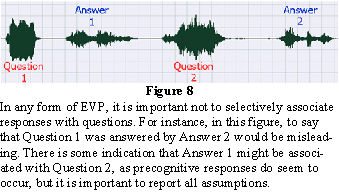

In transform EVP, the utterance typically occurs before the next question or comment. In some instances, convincing evidence has been reported suggesting that some utterances precede the question, as if anticipating it. (An alternative explanation to precognition is that the experimenter anticipates the question by mentally composing it before speaking, and that mental processing is detected and responded to.)

In transform EVP, the utterance typically occurs before the next question or comment. In some instances, convincing evidence has been reported suggesting that some utterances precede the question, as if anticipating it. (An alternative explanation to precognition is that the experimenter anticipates the question by mentally composing it before speaking, and that mental processing is detected and responded to.)

It would be considered a Best Practice to never associate utterances occurring before the preceding question and after the following question with the question. For instance, as is illustrated in Figure 8, Answer 2 would normally not be associated with Question 1.

Opportunistic EVP poses unique problems for question and answer associations, and the question of appropriate associations should be addressed in this article. For instance, asking a question and simply allowing the sweep to continue until a likely answer is heard does not seem to allow for the old question as to whether or not a typing monkey will eventually produce meaningful text.

Techniques for Eliminating False Positives

A “false positive” is the assignment of “EVP” status to mundane sounds. This would include imagined (Figure 2) and mistaken (Figure 3) results in transform EVP, and mistaken results (Figure 6) in opportunistic EVP. It would also include inappropriate association of questions and answers. The challenge is to find a way to experimentally establish that both categories of EVP formation actually produce EVP. Next is the task of finding a way to distinguish true EVP from mistaken and imagined results.

Transform EVP

In transform EVP, the known sources of false positives are:

- Radio-frequency contamination

- Unnoticed voices or voice-like sounds in the environment

- Recorder artifacts

- Imagination of the listener

Radio-Frequency Contamination

RF contamination is usually pretty obvious because it produces unusually long messages that are often cut-off as incomplete expressions or which are nonsensical when the circumstances of the recording is considered. Digital wireless devices such as cell phones, wireless servers, most wireless land-line phones and baby monitors using security codes will not produce an intelligible signal in RF contamination. Frequency Modulation (FM) radio will not produce intelligible contamination, as with broadcast television. The only realistic source for such contamination is AM radio.

Research has shown that EVP can be recorded even when the recorder is shielded from RF contamination, so it has been empirically shown that transform EVP are not caused in that manner. (8) (9) Nevertheless, RF contamination is a possible cause of mistaken results, and this source of false positives must be accounted for. The most effective way to avoid any of the false positives in EVP is described in the Best Practice: Characteristic Test for EVP. (2) In that practice, common characteristics of EVP which have been anecdotally identified via long-time experience within the community and empirically via controlled experiments are used as a norm for EVP. If an utterance falls outside of that norm, then it is considered suspect. It is always recommended that practitioners set aside suspect EVP until more evidence is available.

Unnoticed Voices or Voice-Like Sounds in the Environment

This is a bigger problem than might be expected. It is common for a practitioner to make a recording in the field and not review the results until after returning home. For most people, memory is not sufficient for knowing whether or not voices in recordings were from physical people speaking elsewhere in the environment.

The recommended solution for this is the use of a second recording device as a “control.” (10) Two important characteristic of EVP are that the exact same utterances is never recorded in more than one recording circuit at the same instant, and that higher quality recorders are less likely to record an EVP. As such, a simple solution is to require that field recording be done in tandem with a second, higher quality recorder such as is found in a video camera. This is a Best Practice titled: Using a Control recorder for EVP.

Recorder Artifacts and Imagined EVP

The less expensive digital voice recorders are thought to be so successful in EVP experimentation because of the noise generated within the recorder, presumably in the analog input stage. It is often unnecessary to supply background noise. At least with the earlier models, they were also subject to bursts of noise that are reminiscent of an angry man yelling a message. Further analysis has shown that the bursts of noise are simply artifacts, but that the communicating entity sometimes uses the sound to form voice. Since the sound naturally has an angry sound, the resulting EVP sounded angry.

Other artifacts include induced noise from nearby electrical devices. The induced noise has a frequency of equal to power-line frequency, two times line frequency or a harmonic of line frequency, and it can be modulated to sound like voice by moving the recorder in relationship to the source.

Protection from false positives of this kind is the characteristic test (2) and a listening panel. The intention of a listening panel is that people experienced in hearing EVP should be able to agree with what the utterance is thought to say without prompting. The EVP online listening trials report details the results of double-blind listening trials. In the trials, 25.2% of the words were correctly identified by website visitors. The examples are considered Class A that should be correctly heard 100% of the time by an experienced listener. In fact, a not exactly the same experiment was conducted for the same examples using more experienced ATransC members with estimated average correct word recognition of 74%.

Mistaken Results in Opportunistic EVP

When radio-sweep is configured with a direct connection to a recorder or recorder program, both radio-sweep and EVPmaker are closed to ambient voice, and therefore, unnoticed voices in the environment are not a consideration. However, understanding random sequences of audio bits as EVP is a problem, the extent of which is unknown. I am not aware of any empirical studies that have been conducted to establish a standard for accepting results.

In what has been “normal” experimentation by individual researchers, the question of how to avoid false positives has not been an issue except in the case of radio-sweep. This has been true because most researchers have gained a reasonable level of experience and have developed an “ear” for understanding the utterances. Today, we are seeing more and more people begin their experience with EVP by using the radio-sweep devices or EVPmaker software. The resulting lack of experience is producing false positives that are too often being accepted as genuine EVP.

On behalf of the ATransC, we recommend that all people new to trans-etheric communication learn to record for EVP using the basic recorder technique. Then, after learning how to record EVP and how to recognize false positives in that way, we encourage people to try other methods. The field has progressed, but it may be true that the basic recorder technique is not ultimately as productive as other techniques, so it is important that people try approaches such as radio-sweep. Beyond the desire that people should not believe something that is not true, we are concerned with the damage to the entire field of study that can be caused by a large population of people claiming EVP that are seen as false positives.

Testing to Identify False Positives

Currently the content of the message is the primary test for determining a false positive, but even that seems to require modification to accommodate the kind of results being reported with opportunistic EVP. For instance, it is common for the practitioner’s name to be spoken in the results while this is much less the case with transform EVP. The messages are potentially endless while an important characteristic of transform EVP is that they are relatively short. It is also difficult to distinguish which possible utterance is associated with which question put by the practitioner while transform EVP is pretty clearly a question and answer response as in normal communication.

While these differences pose a problem for avoiding false positives, they may also tell us something about how EVP are formed. For instance, if the experimenter’s name is being called out more often in opportunistic EVP, why is there a difference?

A potentially inflammatory question that needs to be addressed is why there is so much more social tension associated with opportunistic EVP than is associated with transform EVP. For some experimenters who report extraordinarily long messages, the communication has turned to predictions of doom that have not been fulfilled. EVP is as much about the person as it is about the technology, so these questions do need to be asked and answered in a candid, but analytical way.

References

- Gullà, Daniele, Computer–Based Analysis of Supposed Paranormal Voice: The Question of Anomalies Detected and Speaker Identification, Interdisciplinary Laboratory for Biopsychocybernetics Research, Bologna, Italy, atransc.org/gulla-voice-analysis/

- Butler, Tom, Characteristic Test for EVP, ATransC, atransc.org/characteristic-test-for-evp/

- Butler, Tom, Formation of EVP, Association TransCommunication, atransc.org/evp-formation/

- Pareidolia, Wordspy, wordspy.com/index.php?word=pareidolia

- Paranormal Systems, (Website missing as of 9-23-2016)

- Guiley, Rosemary Ellen, Frank’s Box, Paranormal Insider, Paranormal Systems, (Website missing as of 9-23-2016)

- Bion, Stephan, EVPmaker, evpmaker.software.informer.com/

- Weisensale, Bill, Eliminating Radio Frequency Contamination for EVP, ATransC, atransc.org/eliminating-rf-contamination/

- MacRae, Alexander. “Report of an Anomalous Speech Products Experiment inside a Double Screened Room.” Journal of the Society for Psychical Research. 2009. Society for Psychical Research. sgha.net/library/MacRaeAnomalousSpeech.pdf

- Best Practices, Control recorder for EVP, ATransC Collective, atransc.org/using-a-control-recorder-for-evp/

![]()

1 thought on “Locating EVP Formation and Detecting False Positives”