Also at ethericstudies.org/sharing-evp/

These practices are recommendations provided under the

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

Sponsor(s)

Tom Butler

Abstract

The phenomenal voices of Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVP) are typically classified in terms of how well an untrained listener can be expected to understand the utterance. Research is showing that, on average, a listener will only make out up to 25% of Class A examples without prompting. Yet, practitioners commonly post Class C examples on the Internet in forms that even experienced listeners find difficult. This practice includes recommendations intended to guide practitioners in ways of sharing examples with the public that offer listeners the highest likelihood of understanding what is said.

Introduction

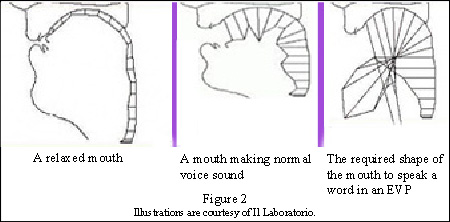

Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVP) are formed by transforming available audio-frequency noise into voice or via some form of selection of available voice fragments. Either way, the resulting audio-file contains voice which is an approximation of the human voice it is supposed to represent. Allophones which form the voice are often oddly arranged and the usual auditory cues may be misplaced from what the listener has been culturally trained to expect.

A good assumption for everyone concerned with these phenomena is that practitioners hear their examples as they report. The problem is that good examples of EVP for comparison are not commonly available, and there are too few qualified listeners willing to deal with the social-technical issues surrounding critiques. This leaves most practitioners alone in determining what are and are not EVP. And in fact, there is substantial evidence that people who are new to EVP are often mistaken about the quality of their examples.

A classification system indicating how well a listener can be expected to hear and understand examples of EVP has been shown to help practitioner grade their examples, The classification system used by ATransC is:

Class A: Can be heard and understood over a speaker by most people

Class B: Can be heard over a speaker but not everyone will agree as to what is said

Class C: Can only be heard with headphones and is difficult to understand.

Class B or C voices may have one or two clearly understood words. Loud does not equal Class A.

Research has shown that, on average, a Class A or B example will be correctly heard and understood only 20 to 25% of the time. That percentage will increase as the listener becomes accustomed to a particular practitioner’s usual examples. It will also increase if the listener takes time to use headphones and listen to the example many times.

Validity of Examples

Probably the two most damaging factors determining how well the concept of EVP is accepted by the general public and whether or not mainstream scientists are willing to study it is the poor quality of examples on the Internet and unsupported claims made by practitioners.

This is not a simple case of, “Well, they are just being silly,” or “They are delusional.” The skeptical community is determined to make the study of anything like EVP seen as a form of pseudoscience. They are already very successful in convincing governments and university that believing in pseudoscience poses a danger to society because it degrades people’s understanding of science and takes undue advantage of unsuspecting citizens. People who seriously study these phenomena and people who display examples to the public are all in the same community and painted with the same brush normally reserved for our least discerning members. The result is little to no support for serious research and rejection of scholarly papers by the mainstream academia.

The following factors should be considered when selecting an example for public display:

Sound Mistaken as Voice

Under the right conditions, a burst of noise or a fragment of voice can be mistaken as a one syllable word. This is especially true if the practitioner is intently listening to every sound in an effort to detect an EVP. Add to that, the likelihood that background noises are present and marginal recording quality, and the possibility of mistaking mundane sounds as paranormal words becomes a high probability. For this reason, experienced researchers will ignore single syllable words in EVP if they are not accompanied by other words or are not clearly in context.

Contextual Utterances

EVP is considered communication between two intelligent personalities. As such, EVP are expected to have some relationship with what is happening in the recording environment, both timeliness and message content. Probably because the communication is between etheric personalities–that of the communicator and the practitioner’s etheric personality–an EVP in response to a question may be recorded before it is spoken but after it is mentally composed. As a general rule, it is expected that an EVP will be recorded within a few seconds (before or after) of the question or incident about which the communicator might comment.

Some technologies for EVP make it a little too easy to simply turn on the process and wait for sounds to be recorded that might be EVP. In this approach, practitioners tend to develop a likely story to explain the EVP. This approach to EVP is referred to as “storytelling” and is commonly associated with mundane sounds mistaken as EVP. The practitioner can assure against the tendency to story tell by maintaining a strict policy of discarding possible EVP that do not conform to question-answer or incident-comment criteria.

Background Sound

The current working hypothesis is that the voice in EVP is formed by transforming available audio-frequency sound energy. Thus it is referred to as “transform EVP.” EVP are thought to be formed in the input, analog stage of the recorder, but otherwise, the recorder is just to make a record of the EVP and the practitioner’s voice.

Experience is showing that a microphone is only important to introduce additional noise if the noise generated internally by the recorder is not useful for voice formation.

A very high-quality recorder produces very little internal noise but a low-quality recorder typically produces too much steady-state noise, which is not useful for EVP.

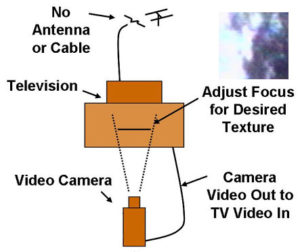

Current understanding is that noise in the voice range–400 to 4,000 Hz–with many perturbations, such as small noise spikes, is useful for voice formation. The noise is needed for voice, but the perturbations are apparently useful to initiate the voice formation process.

The Panasonic RR-DR60 produces this kind of noise internally, but it is possible to produce it externally. One technique is to rapidly sweep a radio dial. This is not radio-sweep as used in ghost or spirit boxes. That technique sweeps the dial in two to four seconds and may produce whole words in the output file. The ATransC does not consider the result of radio-sweep to be EVP. The objective is to sweep the entire dial in under a second so that no whole words or even allophones can be detected. The objective is the resulting noise and not the “whole” sounds.

Sounds from a common fan, running water or passing cars have been shown to be “dirty enough” to produce EVP.

Selective Reporting

If the practitioner selects seemingly meaningful sounds out of a stream of sounds while ignoring other, less seemingly meaningful ones, then that is referred to as “selective reporting.” This is especially a problem with radio-sweep and EVPmaker techniques.

Radio-Sweep

A special case of EVP is what is commonly known as radio-sweep. This involves manually or automatically sweeping a radio dial to produce sound fragments which are present when consecutive radio stations are momentarily connected to the output sound stream. Voice fragments, music, silence and miscellaneous noises are typically part of the output stream, and since most radio-sweep devices sweep the dial in seconds, entire words are often in the output.

Current research is showing that radio-sweep probably does not produce EVP. [1] [2] Virtually all forms of EVP are either transform (voice formed out of noise) or opportunistic (words formed by selection of existing words or parts of words). Radio-sweep messages claimed to be paranormal are found in voice fragments which are necessarily formed in pre-scheduled programming at the moment the sweep intersects that station.

The question or situation, the time the sweep is conducted and the moment the sweep intersects the station must all occur to produce the intended fragment of voice. If the sweep is too slow, then whole words are detected. If it is

even slower, then whole phrases can be detected. These words or phrases must be what are required for the intended message. If not, then the announcer must be coaxed into saying the required words at the required moment. There is no precedence indicating the etheric communicators are willing to impose their will on people in this manner.

Based on listening tests, claimed radio-sweep EVP are either transform EVP resulting from manipulation of noise naturally resulting from the sweep, or normal sounds mistaken as paranormal. Storytelling is a major problem, as is selective reporting.

Live Voice

Pre-recorded speech is sometimes used as the input sound source for transform EVP. Speech in a different language is most popular, but as is seen in radio-sweep, any speech is liable to be used. As it turns out, many naturally occurring phrases sound like English phrases and it is easy to inappropriately attribute paranormality without careful comparison of input and output files.

The Butlers conducted a study of the use of live voice for EVP by comparing input and output files for multiple session. Each session produced what was heard as an EVP transformed from the input; however, on closer examination, every example turned out to be naturally occurring foreign-language speech that sounded like an English phrase.[3]

The ATransC recommends that, if live voice is used as the input file or sound source for EVP, suspected EVP should be compared to the section of the input file that is thought to have been transformed. If the two files are essentially the same, the example should be rejected. Also, suspected EVP should be rejected if the same “transform” is seen to have occurred in more than one session.

Practice

A precondition for sharing EVP with the public is that the practitioner must have a sense of what is said in the example and that this has been supported by some kind of EVP Listening Panel of uninformed people. It is not enough to find someone who will agree with the practitioner. It is important that the listener is not influenced by what the practitioner believes is said.

When sharing examples of EVP with the public, the objective is to assure the examples are correctly heard and understood. To accomplish this, the practitioner should present examples in a form that allows listeners to adjust volume, repeat segments and distinguish between the target voice and peripheral sounds. Recommendations to accomplish this include:

- Isolate the EVP and possibly a little of the practitioner’s voice so that it is clear that the listener is hearing the EVP and the obvious voice of the practitioner (alternatively, someone or something the listener has been told to expect).

- Present one example or phrase per sound file. A very long sound file with many sounds can be very confusing, making it difficult for the listener to know which sound is supposed to be the EVP.

- The average sound file should be less than thirty seconds.

- Avoid over processing the sound file. Changing speed, noise reduction, frequency selection and over amplification can change the intended meaning of EVP or make mundane sounds seem to be EVP. Extreme amplification is likely to make radio-frequency contamination audible.

- If live voice is used, provide a comparison between the input and output files for the isolated EVP.

- In all cases, explain how the recording was made and what has been done to the file.

Example Application

This practice is applicable to any situation in which examples of EVP are shared with the public. When used as part of the practitioner’s routine, it will help assure that the practitioner does not fall into the trap of self-delusion that so often occurs with people new to EVP.

It is important to note that this practice is intended for use when sharing examples; however, it is not uncommon for people to record only for themselves, and to practice a kind of mental mediumship aided by EVP, whether it is clearly understood or not. EVP can be a personal tool for communication with loved ones, and while it is good that a person does not make a habit of mistaking the ordinary as phenomenal, sometimes the healing that occurs with belief that contact has been made trumps best practices.

References

- ↑Leary, Mark. A Research Study into the Interpretation of EVP, atransc.org/radiosweep-study2/. ATransC Online Journal, 2013.

- ↑Butler, Tom and Lisa. Radio-sweep: A Case Study, atransc.org/radiosweep-study1/. ATransC Online Journal, 2013.

- Butler, Tom and Lisa. Using Live Voice Input Files. ATransC, atransc.org/live-voice/.

Also at

Also at

A case study to illustrate this point is based on comments about darkroom séances reported in the ATransC NewsJournal. A person who was knowledgeable about EVP commented that “It seems fake to me.” He went on to say that “I believe there is a trap door or something like it. Notice that he’s behind the curtain for no real reason other than to shield eyes from whatever he’s doing. He may be an escape artist. He may have an associate sneak in from the floor or wall, etc. If he hid a small speaker in the wall outlet it could sound like this. He literally could have someone in another room speaking into a wireless mic and then it can be projected through the hidden speaker.”

A case study to illustrate this point is based on comments about darkroom séances reported in the ATransC NewsJournal. A person who was knowledgeable about EVP commented that “It seems fake to me.” He went on to say that “I believe there is a trap door or something like it. Notice that he’s behind the curtain for no real reason other than to shield eyes from whatever he’s doing. He may be an escape artist. He may have an associate sneak in from the floor or wall, etc. If he hid a small speaker in the wall outlet it could sound like this. He literally could have someone in another room speaking into a wireless mic and then it can be projected through the hidden speaker.” Moving the chair, and the usual rearranging of his clothes is a common demonstration of phenomenal control in David Thompson’s seances. It is difficult to put into an evidential perspective. However, at the end of the darkroom demonstration Stewart Alexander provided during the 2011 Stewart Alexander and Friends Conference, the Butler’s witnessed the glow tabs on Stewart’s knees passing by at eye level, less than a foot from their face. Others who were further around the circle, saw the tabs tilt dramatically as Stewart’s chair floated around the room. He had been partially awakened for the experience and complained something to the effect, “I really do not like this part.” Later, with the lights on, Stewart’s undershirt was found lying on the floor.

Moving the chair, and the usual rearranging of his clothes is a common demonstration of phenomenal control in David Thompson’s seances. It is difficult to put into an evidential perspective. However, at the end of the darkroom demonstration Stewart Alexander provided during the 2011 Stewart Alexander and Friends Conference, the Butler’s witnessed the glow tabs on Stewart’s knees passing by at eye level, less than a foot from their face. Others who were further around the circle, saw the tabs tilt dramatically as Stewart’s chair floated around the room. He had been partially awakened for the experience and complained something to the effect, “I really do not like this part.” Later, with the lights on, Stewart’s undershirt was found lying on the floor.